Medill Cherubs embrace ‘For the Left Hand’

What happens when some of the world’s brightest young journalists gather to watch “For the Left Hand”?

An outpouring of tears, laughter, conversation – and an avalanche of questions.

Each summer, high-school reporters and editors from around the globe converge in Evanston for the Medill-Northwestern Journalism Institute, a long-running program informally known as Medill Cherubs.

I was a Cherub in the summer of 1971 and have returned uncounted times to share my books, films and career highlights with young colleagues. No audience I’ve encountered anywhere in the world has been more enthusiastic, open-minded or intellectually and emotionally engaged.

That was apparent again on June 28, when I screened “For the Left Hand” at Medill’s Evanston campus for the 84 Cherubs selected from more than 200 applicants for this year’s program. Because this was the first time the Cherubs met in person since the pandemic, the occasion felt especially significant.

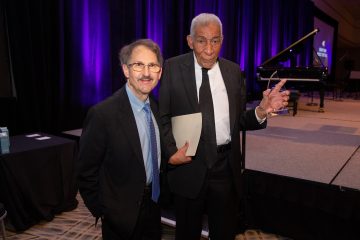

Medill educator Roger Boye – who has directed Medill Cherubs for decades – introduced me to the students and insisted that I show everyone the purple-and-white Medill-Northwestern socks I wore for the occasion (yes, a gift from a previous appearance). The rather splashy pattern elicited cheers.

Then the film began, the students witnessing Norman Malone – a man old enough to be their grandfather – attempting one of the biggest challenges of his long life: playing Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the Left Hand with Orchestra on the week he turned 79.

The instant the credits finished – and even before the lights came up – the students unleashed a torrent of applause, followed by a sea of hands that shot up to ask questions when I took the stage.

These students’ inquiries said as much about their own perceptiveness as it did about how much the film meant to them. Among the highlights of our dialogue:

Q: “How did you decide what to include in the film?”

A: We had about 140 hours of footage, which we whittled down to 75 minutes. I worked with directors Gordon Quinn and Leslie Simmer, and producer Diane Quon, to incorporate only the most riveting, impactful footage – but always in service of unfurling the narrative.

Q: “How did you get Norman to open up?”

A: If I had to sum up in one word what we journalists must establish with an interviewee, it’s this: trust. You achieve that by doing more listening than talking; by looking your subject in the face; and by being as open and accessible a person as possible.

Q: “What happened when you showed Norman the final product?”

A: Here’s where newspaper journalism and documentary filmmaking diverge. “For the Left Hand” originated as a Chicago Tribune series I wrote in 2015. With newspaper stories, we never show the subject the article before it’s published, because they must have no influence on the finished piece. In documentary, Kartemquin Films – which produced “For the Left Hand” – shows the subject the film when it’s nearly complete. Why? Kartemquin founder Gordon Quinn explains that the subject must have a voice in telling their own story. I’ll never forget what Norman said after he watched the film: “I can see my age, I can see my disability. And I can choose to accept that or reject it. I accept it.” Norman asked for no changes to the film.

Q: “When you’re working in film or in articles, how do you stay objective, especially when the topic is as emotional as ‘For the Left Hand’?”

A: I don’t try for objectivity. I strive for truth.

There simply wasn’t enough time to answer all the questions, so Medill Cherubs director Boye eventually returned to the stage to bring the formal part of the evening to a close. Then he presented me with a Medill sweatshirt, which I put on immediately.

Finally, I invited students to come onstage with me and continue the conversation – and we kept going until they had to be back in their dorms by 10 p.m.

Many of the students’ questions have clung to me, especially one: “How did making this film change you?”

I don’t know if it has changed me, but it surely has shown me the power of storytelling to change lives for the better. After the newspaper series was published, Norman began receiving invitations to give piano performances for the first time in his life! The film’s release only heightened his profile, so that today he hardly can go into Chicago’s Orchestra Hall without being recognized by his fans.

No one deserves the recognition more.